Greater Magadha and the Origins of Hinduism

While I was doing the research for my post on the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC), I came across the works of the Finnish Indologist Asko Parpola, and further digging led me to the Dutch Indologist Johannes Bronkhorst. I ordered copies of their books, The Roots of Hinduism and Greater Magadha, and I am going to summarize some of their findings in this post. Bronkhorst’s Greater Magadha was of particular interest, since it delved into the history of the Eastern Gangetic Plain, which is part of the country where my ancestors come from. Their work also sheds light on a mystery regarding the genetic makeup of the present day Indian population that was discovered recently by Robert Reich and his collaborators.

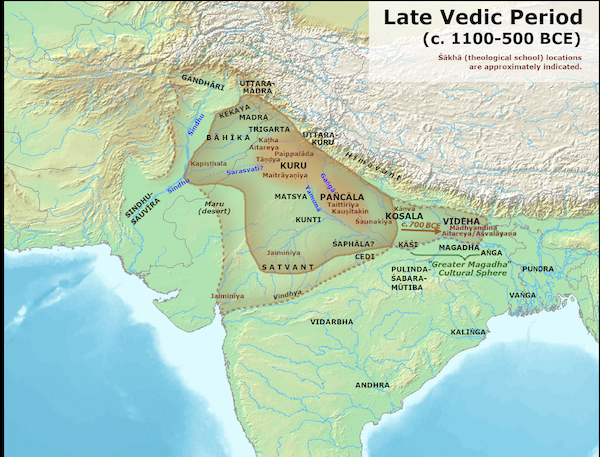

The traditional history of Ancient India states that Buddhism arose around the 5th century BCE within a culture that was predominantly Vedic Hindu, and was a reaction to issues such as the caste system and excessive emphasis on rituals that existed within Hinduism (this has often been compared to how Protestanism separated out from Catholicism in medieval Europe). In contrast to this, Bronkhorst argues in his book that two distinct cultures existed in Northern India until the period close to start of the current era. Buddhism, Jainism and a religion called Ajivikism (that is now extinct) arose in the cultural environment that existed in the region to the East, referred to as Greater Magadha, within the context of religious beliefs that existed in that culture, as opposed to the Vedic culture to the West. Both these cultures spoke Indo-European languages and were offshoots of a mixed culture that arose as a result of the mixing of the IVC people and the Indo-Europeans who had come into the sub-continent in the period 2000 BCE to 1000 BCE. The culture to the West was found in the kingdoms of Kuru-Pancala and was located in the area called Doab, between the Ganga and the Yamnuna rivers. The culture to the East was associated with the Kingdoms of Magadha, Videhla and Kosala and comprised the regions of present day Eastern Uttar Pradesh and Western Bihar. After staying apart for several hundred years, the merger of the two cultures took place in the period between the second century BCE (at the end of the Mauryan period) and the second or third century CE and resulted in the Classical Hindu Culture that has come down to modern times. This leads to the interesting question: Why did two distinct cultures exist in the first place? I will discuss this later in this post.

Religious Practices in Greater Magadha

According to Bronkhorst, the biggest distinction between the Western and Eastern cultures was in the area of religious practices (there were other distinctions as well that are discussed in the following section). The Western culture was Brahmanical based on the Rigveda, and featured a Caste system in which the Brahmins were accorded the highest status. The Greater Magadha culture on the other hand rejected Vedic philosophy and the caste system. It developed religious practices of its own that were very distinct from Vedic Brahamanism, and served as the birthing ground for the religions of Jainism, Buddhism and Ajivikism. The Greater Magadha area was also responsible for the so called second-urbanization in India (after the IVC) with cities such as Patli-Putra and Rajgriha established, and also birthed the Mauryan Empire that carried out the first great unification of the country.

The idea of re-birth and karmic retribution, i.e., the belief that we have an inner self or soul that goes through multiple births, and the form that we assume in our future births is influenced by how well we have lived our current or past lives, was something that arose within the religious traditions of Greater Magadha. This belief in turn influenced the three major religions that came out of Greater Magadha, all of whom came up with ideas by which karmic retribution and the endless cycle of rebirths could be addressed. Bronkhorst is of the opinion that these beliefs and practices were not confined to these three religions only but were more widely dispersed within the society and formed part of the spiritual culture of Greater Magadha. He argues that the original Vedic religion as described in the Rigveda and other Vedic texts did not incorporate a belief in rebirths or karmic retribution, and these were adopted into the Hindu scriptures after the two cultures fused together.

We start with brief descriptions of Jainism, Ajivikism and Buddhism:

The early Jain religion believed that it was possible to atone for the sins of past lives, and also put an end to the cycle of re-births by way of painful ascetic practices, such as ceasing all activity, physical as well as mental, and remaining motionless for long stretches of time (sometimes even starving oneself to death). The logic behind this belief was that by suppressing all activity there would be no new deeds that can lead to future karmic retribution, and the suffering caused due to these practices would lead to the destruction of traces of earlier deeds that have not yet suffered retribution. Hence the way to liberation from the cycle of re-births was through hardship and suffering. This kind of ascetism was undertaken towards the end of ones life, when all other responsibilities have ended.

Ajivikism was closely related to Jainism. There are no existing texts that have survived from this religion, and the last practioners died out about a thousand years ago. Historians have been able to recreate some of their doctrines by examining the criticism of Ajivikism in Jain and Buddhist texts, and based on this the following is known about this vanished religion: Ajivikists also believed in rebirths and karmic retribution, but unlike Jains they did not think that cessation of all activity would lead to annihilition of former actions, so karmic retribution due to past actions cannot be avoided. On the other hand Ajivikas shared with Jains the belief that non-performance of new actions will avoid karmic effects in future lives. However it won’t end the cycle of rebirths, which will continue over the course of multiple eons until it reaches its natural ending and nothing we can do in our current life can change this.

The Buddhists rejected the idea of extreme asceticism of the Jainas in order to achieve salvation. They believed that the real problem is not in one’s acts, but the driving force behind these acts, which they identified as desire or intention. Unlike the Jainas for whom physical activity was central, for the Buddhists it was mental activity or more precisely the intention behind our thoughts. Hence achieving salvation is a psychological process of eliminating all desires, not just immobilization of the body and mind or knowledge of the true nature of self. For Buddhists suppressing the intention behind mental activity was more important than ceasing all mental and physical actions. In some sense the Buddha changed the nature of the debate in a new direction, and away from its Greater Magadhan roots.

There was another current of religious thought in Greater Magadha that is not expressedly present in Buddhist or Jain literature, but these religions were nevertheless aware of it. This is the idea that it is possible to reach liberation, by insight into the true nature of ones self. This idea is best expressed in the Hindu texts such as the Bhagawad Gita, but Bronkhorst believes that it may have older Greater Magadhan origins. As evidence he points to the existence of the idea of a ‘true self’ which is inactive, and not affected by the activities of the body or mind, in Ajivikism. Knowing the true nature of ones self means no longer identifying with the activities of body and mind. Since it is the ‘true self’ that goes through multiple re-births, this explains their belief that our actions cannot prevent this from happening. The Buddha was also aware of the idea of a true self, and explicitly rejected it in one of his sermons, which adds credence to the belief the idea was part of the religious currents within Greater Magadha.

After this short description of religious practices in Greater Magadha, we now discuss how these interacted with the Brahminical tradition in the Western region. It so happens that the form of ascetism with its emphasis on the cessation of bodily and mental actions is mentioned in early Brahmanical tests such as the Katha Upanishad which are thought to have been composed around 800 BCE. In Part II of his book, Bronkhorst does an extensive analysis of these texts, and comes to the conclusion idea of rebirth and karmic retribution in these early Upanishads was not native to the texts but was borrowed from external sources. He also does a detailed analysis of the chronology of that period to show that the early Upanishads (which have the most mentions of the re-birth doctrine) were actually composed later than thought, and may have been in the same era as the of the Buddha, so they were probably influenced by Greater Magadhan culture. This idea has also been proposed by Asko Parpola in his book, but is not universally accepted by other experts, for example see this review of Bronkhorst’s book by Alexander Wynne.

Religious beliefs in the Greater Magadha area were dominated by Jainism, Buddhism and Ajivikism until the end of the Mauryan dynasty in the second century BCE. For example the Emperor Chandragupta Maurya was a Jain, while Ashoka is famous for spreading Buddhist beliefs far and wide. However, after this Empire ended, there was a merger in the religious and cultural practices of the Western and Eastern regions, which culminated in the creation of the current Hindu religion. It resulted from a merger of ideas from Greater Magadha into the traditional Vedic religion, as well as the spread of Varna and Jati based caste system into Greater Magadha. Bronkhorst proposes that the epic Mahabharata assumed its present form while this merger of cultures was going on, and one of the objectives of the writers of this Epic was to ease this integration. They did so clearly specifying the caste duties associated with the four varnas, including making sure the Kshatriya rulers behaved in accordance with Brahmanical expectations (apparantly the Mauryas neglected to do this). They also incorporated ideas from the Greater Magadhan religions into the Mahabharata, and especially into the Bhagawad Gita.

The Gita propounds on the following ideas that have Greater Magadhan roots:

- The Gita teaches the concept of a Self that does not participate in, and is not touched by ones actions. It rejected the idea that just inactivity enough to bring about salvation, since the core of ones being is in this Self and does not act. Hence the idea of karmic retribution is based on a misunderstanding, since deeds are carried out by the body and mind, neither of which is identified with the Self, which is different from both of them. Attaining knowledge of the true nature of the Self is an alternative way to obtain salvation. Liberation from the effect of one’s actions is possible, since in reality no actions are ever performed (by the self) and this knowledge is sufficient to obtain liberation! This is called jnanyoga or the ‘discipline of knowledge’, which could be acquired by the practice of meditation (as opposed to physical austerities). Another way is the karmayoga or the discipline of action.

- The Gita teaches that if duties are performed with the right attitude, then there is no involvement of the Self. In order to do so, actions must be performed in complete dis-association with the fruits of those actions (such the desire to obtain happiness or avoid suffering) do not produce karmic effects and are as good as complete inactivity. Once this state is reached and since there is no involvement of the Self, the body (and mind) have a nature of their own that determine their activity. But what is this activity? The Gita suggests that the appropriate activities are those that correspond with ones ‘own duty’ or svdharma. This is different for the four varnas and corresponds to their caste duties. Hence it is implying that if the caste prescribed duties are performed with the right attitude, it does not matter what those actions actually are.

The Mahabharata has other passages that show familiarity with ideas from Jainism and Ajivikism (Buddhism is ignored for some reason), but not in a refined form and in one place refers to them as being non-Vedic in origin. There must have been some amount of internal opposition within the Western Vedic tradition to these ideas from Greater Magadha and there are some Vedic texts that reflect this. For example there are some important Vedic schools such as the Mimamsa that have no mention of karmic retribution at all. Bronkhorst also mentions several Vedic schools such that of the Carvakas that outright rejected this idea.

Other Differences Between the Two Regions

Bronkhorst points out the following other differences between the Western and Eastern cultures:

- Brahmins lived on both sides of the cultural divide, but a different social order existed in Greater Magadha in which the Kashatriyas were accorded greater status. As a result Magadhans are almost universally derided in all of Brahmanical literature. They in turn referred to the Brahmins as ‘charlatans and fools’.

- The Greater Magadhans constructed burial mounds that were round, in contrast to the four-cornered versions that existed in the West. These round mounds gave birth to the Stupas that we find in Buddhist sites in later times and this practice was shared by Jainism as well. An early Brahmanical text called the Satapatha Brahmana talks about this distinction. They looked down at the practice of constructing round mounds and associated it with Godlessness and social disorder.

- According to Megasthenes, the Greek Ambassador to Chandragupta’s court in the 3rd century BCE, there were two types of ascetics (or sadhus) in India during that time, the Brahmanas and the Shramanas, with distinct practices (page 92, 107). Sramanas were associated with Greater Magadhan culture, they shaved their heads and facial hair, lived in groups, depended on alms and engaged in intense meditation and fasting in their religious practices. In contrast the Brahmanas ascetics let their hair and beards grow long, wore antelope skin and engaged in Vedic rituals.

- The speech patterns (or accent) of the people to the East was different than their Western counterparts. It is interesting that this cultural divide has continued on to the present time, with the speech accent of people from Bihar or Eastern Uttar Pradesh being instantly recognizable (and often derided by other Northerners).

- According to Kenneth Zysk (1991) Ayurvedic medical practices did not originate in Vedic religion, their roots lie in Jainism and Buddhism, i.e. in Greater Magadha. The medicinal practices described in the Vedas involved sorcery, spells and amulets, while Jain and Buddhist literature talks about using diet, ointments and poultices for healing which is more in line with the rational therapy in Ayurvedic medicine. Based on observations of Indian healing practices by Magasthenes, Zysk concludes that these two distinct ways of doing medicine co-existed in India in the late-Vedic period, and the one way this could have happened was if they occupied distinct geographical areas.

Why Were There Two Cultures?

Brankhorst’s book raises an interesting question: If indeed his thesis is correct that there were two distinct cultures that existed in the region of the Ganges plain in the first millennium BCE, then what was the historical reason for this? The two cultures continued next to each other for at least five or six centuries, if not longer, before their merger happened. He speculated that perhaps the initial settlers arrived in the North Indian plains in two separate waves thus giving rise to the two cultures. This theory has received support in Asko Parpola’s book The Roots of Hinduism where he proposes the following scenario:

- Indo Europeans arrived in the Indus Valley in two separate waves. The first wave happened in the period 1900-1700 BCE, while the second wave was in the period 1400-1200 BCE. The first wave was settled in the Indus Valley and the integration with the IVC inhabitants was well underway when the second wave arrived. During the interval between the two waves, there was a cultural shift from the ancestral Indo European religion due to the interaction with the culture of the IVC. An archaic version of the Atharvaveda contained the religious beliefs of the first wave (as modified by the IVC), while the religion of the second wave is captured in Books 2 to 7 of the Rigveda.

-

An initial merger of the two waves happened in the Indus Valley and in the Northern Ganges plain around 1000 BCE and was codified in the texts of the Vedas. The Atharvaveda was re-written to conform to the beliefs of the second wave. The Rigveda was also modified as a result of the merger and as a result ended up with two distinct portions: The original Rigveda of the second wave is contained in Books 2-7, while Books 1 and 8-10 contains material that is similar to that found in the Atharvaveda and presumably came from the first wave people. Parpola came to this conclusion by analyzing the language of the two Vedas. He found that the Books 1, 8-10 of the Rigveda and the Atharvaveda were composed in a form of Sanskrit that was older than the Sanskrit that was used for Books 7-10 of the Rigveda. The newer version of the language developed in the Central Asian homeland of the Indo-European tribes in the period after the first wave inhabitants had already left the region. As Parpola puts it in this interview:

My conclusion is that the Vedic literature and religion results from the fusion of two major waves of Indo-Aryan speakers coming from Central Asia to South Asia. The old core of the Rigveda, the hymns of the “family books” II-VII, represent the tradition of the later wave, which arrived around 1400-1200 BCE, and brought with them the cult of God Indra, worshipped with Soma sacrifice. The tradition of the earlier wave, coming to South Asia already around 1900-1700 BCE, infiltrated into the Rigveda in its late books I and VIII-X, but is best represented in the Atharvaveda.

- The people of the second wave moved into the Eastern Gangetic Plain earlier than the first wave, and before the merger between the two had happened in the North. These early migrants were responsible for the culture of the Greater Magadha region.

This theory explains why the Greater Magadhans did not believe in the orthodox Vedic religion that were developing in the North, and went on to develop their own heterodox religious beliefs that were to serve as the seeding ground for the religions of Jainism, Ajivikism and Buddhism. These ideas in turn were absorbed into Brahmanical Hinduism after the fall of the Mauryan Empire around the end of the 1rst millennium BCE.

This theory raises the tantalizing possibility that the reason the first and second wave cultures were so different was due to the fact the first wave people integrated with the inhabitants of the IVC to a greater degree, since they were first to arrive to the sub-continent during the waning days of the IVC, and lived there for several hundred years before the second wave arrived. Thus it could be that some of the core beliefs of the Greater Magadha religion have their origins in the IVC. Since several of these beliefs became part of core Hindiusm after the Western and Eastern cultures merged, this lays out a path by which the ancient IVC religion has influenced modern day religious practices.

There is another very interesting clue to this historical puzzle that was uncovered as a result of the genetic analysis of the DNA of modern day Indian population. This is discussed in the paper Genetic Evidence for Recent Population Mixture in India by Robert Reich et.al. and their findings include:

- Even though modern India has a very large population of over a billion, the people are separated into distinct genetic clusters of a few million individuals each, as a function of the jati to which they belong, of which there are several thousand. Hence people from two jatis living a few villages apart may be as distinct genetically speaking as the Northern Europeans are from the Southern Europeans.

- The reason for the genetic separation is that members within each jati have been practicing endogamy (i.e. marrying only within their groups) for a very long time, as much as 2000 years, which is from around the start of the Christian Era. Prior to this time, during the period 2200 BCE to 100 CE, there was intense mixing between the jatis, but this came to an abrupt halt.

This finding raises the following questions: What was the historical reason the populace was mixing freely during the period 2200 BCE to 100 CE, and why did the mixing stop abruptly around 100 CE? Obviously the caste and jati based restrictions on marriage hardened around 100 BCE, but why did this happen?

The ideas of Bronkhorst and Parpola provide a clue to this mystery. The Indo-Europeans of first wave did not recognize the caste system, and this was also true for people of the second wave. we know this this since there is no mention of the caste system or endogamy in any of the Vedas or other early texts of Hinduism. The caste system probably developed within the culture of the Western region during 1rst millennium BCE, but greater Magadha was not affected by this. As a result the first two thousand years after the arrival of the Indo Europeans was characterized by a mixing within the population groups. This process came to an end in the centuries before 100 CE because this is the period when the merger between the Western Brahmanical and the Eastern Greater Magadha culture was becoming solidified. Hence as the Brahmanical Hinduism took over the Indian sub-continent, it resulted in the strict caste and jati based separation which has lasted until the present time.