A Family’s Transition from Rural Life to Modernity

In the 1950-1960s, Birendra Varma and Shivendra Varma were first cousins working towards their PhD degrees in England, Birendra at the Imperial College in London and Shivendra at the Manchester Institute of Technology. It is hard to believe that just three generations earlier their great-grandfather was a farmer from rural Bihar. Birendra was my father, and this is the story of his family and how they made this transition. In some sense this is also a story of India in the last 200 years, and the changes that were brought about as the country modernized and the people adjusted to a new reality and found their way in a changing world.

I learnt most of this family history from an autobiography that was written by my Grand Uncle Phuldeo Sahay Varma (who was my grandfather’s younger brother and Shivendra’s father). He lived from 1889 to 1981, and having grown up during the waning years of the 19th century he had childhood memories of living in our ancestral village at a time when the family’s main occupation was farming and during the course of his long life he was a witness, as well as a catalyst, of its transformation to urban life. Having resided in two different worlds during his life, he bought a unique perspective to his life story that I found fascinating. He was a very accomplished man himself, a Chemist by profession, and spent most of his life teaching and researching at the Banaras Hindu University and also served the Principal of its new College of Technology. He worked on his Autobiography in the 1960s after he had retired from BHU. A few tens of copies were published that were distributed among the family members. My father had a copy, which has ended up on my bookshelf.

Our ancestors are from the eastern part of the Gangetic Plain, near the confluence of the Ganga and Saryu Rivers. This area has been of key importance in Indian history and served as the center of the Maurya Empire in the 3rd Century BCE, as well as the Gupta Empire a few centuries later. It continued to be an important and prosperous part of India during the last 1000 years under Muslim rule, and when the British came to India, Bengal and this part of Bihar were the first areas that they conquered – this happened during the latter half of the 18th century. Unfortunately, the British also pursued policies that destroyed the local economy including the traditional industry that existed at that time. As well documented in Chapter 5 of Jon Wilson’s book The Chaos of Empire, the economy of this area sank during the 1800s and hasn’t really recovered even now. During the early 1800s, when our family first appears on the scene, farming was the only available profession, and most family members were engaged in it. However, by the end of the century, college education became more widely available and other professions were opening up.

Our ancestral village is called Kausar (or Kaunsar) and it is on the northern bank of the Saryu River, which forms the border between the states of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. The river has moved away from the village now, but at the time when Phuldeo was growing up there in the 1890s, the river ran a few hundred feet from his home. He recalls taking a bath in the river almost daily.

During the late 1700s there were three Kayastha families living in Kausar, ours being one of them. Kayastha is the community to which we belonged, and it has an interesting history which played a part in determining the course of the family’s future. Our family moved to Kausar from village of the Kirtupur in Balia District in Uttar Pradesh. Kirtupur is located 5-6 miles to the south of Kausar. It is not known when this happened, most likely sometime in the 1700s. According to stories Phuldeo heard: Our family was closely associated with a Kshatriya family. Two brothers from this Kshatriya family had a bitter feud, which led to several lives being lost. In order to avoid this violence, some members of the Kshatriya family migrated to Kausar, and our family followed them. As a result, neither of the families owned any ancestral property in Kausar when they started living there.

The first family member whose name we know was Phuldeo’s Great Grandfather (and my Great Great Great Grandfather) Sudarshan Das (1790-1840?). Sudarshan had three sons and two daughters: Among the sons, Phuldeo’s Grandfather was the oldest, his name was Ramroop Lal (1825 - 1910). The middle son was Thakur Lal and the youngest was Govind Lal (1829 - 1914). Phuldeo does not know when Sudarshan passed away (probably happened around 1840) or the cause of his death. When Sudarshan passed away, his children were orphaned since the older female family members were already gone by then and his oldest son Ramroop was still too young to assume responsibility for the family. Sudarshan hadn’t left behind any property that could sustain the family. Fortunately, the boys were saved from becoming destitute by Sudarshan’s daughters who were already married by then, and lived in a nearby village. Ramroop and Thakur went to stay with their sisters, and that is where they completed their schooling. Govind stayed on in Kausar at a neighbor’s home and was not able to go to school.

Ramroop studied Hindi and Kaithi at the village school but didn’t receive any higher education (Kaithi is the script used for the ancestral language Bhojpuri which is spoken in Western Bihar and Eastern Uttar Pradesh). Thakur on the other studied further and became a very good scholar of Farsi and Urdu. However, he passed away shortly after his wedding, as a result of which the study of Farsi and Urdu was banned in our family. This was a very interesting reaction to an untimely death and I had heard of this story when I was growing up in the 1960s (though I didn’t realize then that it had happened almost a hundred years earlier!). As we will see later, there were other untimely deaths in the family before the advent of modern medicine, but this was the only one that caused this kind of reaction. In any case the study of Farsi (or Persian) was associated with getting a job in the administrative apparatus that existed during the time of the Mughals. With the British now in charge, the language to learn was now English, and Thakur lived right at the boundary of when this transition was happening. Colleges teaching English were first established in a few cities in India in the 1860s, so it is likely that Thakur could not have learned the new language even if he wanted to.

The latter-day story of the family is that of using education to move up the economic ladder, but before this could happen, it was necessary to create a financial base to make sure that the family did not become destitute if it got hit by unforeseen events. This was done by Ramroop who established a prosperous farming operation in Kausar and in the surrounding villages. How he was able to do so while starting from scratch must have been an interesting story, but it is not elaborated upon in Phuldeo’s book. Ramroop acquired what was called a Zamindari, which gave him the rights to a portion of the income from the farms in the area (with the rest going to the Government). This system was put in place by the East India Company in the late 1700s, and historically speaking, was one of the main reasons for the impoverishment of the Indian farmer. The Zamindari system was abolished by the Government once India became independent, but by then the damage had been done. The youngest brother Govind was un-educated and never married. He became very skilled in farming activities and the farmers in the village frequently consulted him often on farming related issues. With his help, the output of our family farms increased substantially, and they produced enough grains and produce for the family to live comfortably. At this point in the family’s history (around the 1880s), it seems that they could have continued to farm their fields and continue to live in Kausar. However, this is not what happened, as we see next.

Phuldeo had childhood memories of his grandfather Ramroop since he spent the first twelve years of his life at Kausar, and during this time Ramroop was his main guardian (his father had left for the city with his older brothers by then). Among other things he recalled that Ramroop was a very impressive personality and dominated the social life in Kausar and the surrounding villages. He was a handsome man and was very fond of food, especially anchars (pickles) of various types, and loved to have people over for meals. Indeed, he spent so much in entertaining others, that at the time of his death he left a debt that had to be paid off by the family. Ramroop was very influential in the village, and he served informally as the local judge. This was before the formal Court system was established in that part of Bihar, which happened during the last years of his life.

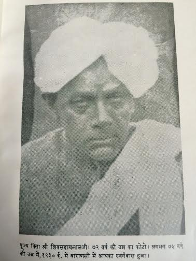

Ramroop had three sons and two daughters. The sons were, from oldest to youngest: Mahabir Lal, Shiv Sahay Lal (Phuldeo’s father and my great-grandfather) and Ramanand Lal. Ramroops’s middle son, Shiv Sahay Lal (1855-1930, in the photo above, taken in the mid-1920s) did his schooling in the village, in Hindi and Bhojpuri.

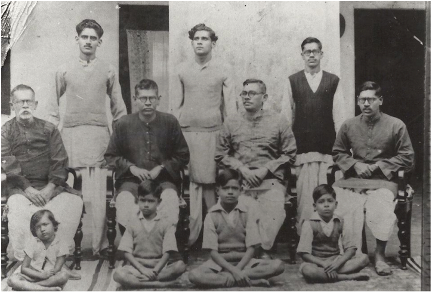

Shiv Sahay in turn had five sons and three daughters. The sons were, from oldest to youngest, and seated left to right in the photo above (which is from the mid 1930s): Gopalji, Baldev Sahay, Indradeo Narayan (my grandfather), and Phuldeo himself (the fifth boy Vishnudeo had passed away before this photo was taken). Sometime during the 1890s, Shiv Sahay made the decision to leave the village and seek a new life in the city. Phuldeo does not explicitly talk about this event in his book, he was probably too young when this happened, but subsequently Shiv Sahay left Kausar for the nearby city of Gaya (famous for its association with Buddhism), with his three older sons. He left Phuldeo and Vishnudeo behind, along with his daughters and wife under the care of Ramroop. Shiv Sahay’s objective was to enroll the boys in a school that offered a modern curriculum, including the study of English. He also had to look around for a job for himself so that he could support them, and fortunately he found one in the District Collector’s Office. His own education had been in the village school in Hindi, but he learnt a smattering of English so that he could support his sons, the first one in the family to do so.

In retrospect this move to the city and decision to get an education in English for his boys was the decisive break that changed the future of our family, and Shiv Sahay was responsible for it. This decision was atypical for the village milieu in which the family resided, indeed Phuldeo reports that there was only one other family from Kausar that tried to educate its children in English at that time, but even they stopped at the 10th grade. After completing high school, two of Shiv Sahay’s boys (Indradeo and Phuldeo) went on to graduate from college and even earned professional degrees. So Shiv Sahay’s bold gamble paid off, and we are all enjoying its fruits. What drove Shiv Sahay to make this move? We will never know the answer to this question, but a possible reason can be the found in the traditions of the Kayastha community to which the family belonged. This community arose probably around a thousand years ago, and its traditional profession was as administrators in the medieval kingdoms of that time, and later during the Mughal Empire. This required the community to be literate, and as a result education was highly valued. We saw this attraction to the administrative services in Thakur’s life story, and even in my own time several family members have opted to join the Civil Services.

So, what happened to Phuldeo after he was left behind in Kausar? He reports that he had a fairly happy and carefree childhood, and since there was no school in Kausar, he remained mostly illiterate until the age of twelve. But at the age of ten, his whole world fell apart. Plague struck the Kausar area twice, in 1900 and then again in 1901 and took away his mother and his three sisters (who were younger than him). He himself came down with a disease that he later identified as Kala Azhar, for which there was no cure at that time. He remained very sick for two years, and barely managed to survive the ordeal. His older brother Vishnudeo, who was still a child, also came down with the same disease, and passed away. One can only imagine the effect of seeing most of the family die must have had on the young boy. His grandfather Ramroop panicked, and as soon as Phuldeo had recovered, he left with him for Gaya to join his father and brothers. Phuldeo later speculated in his autobiography that if it had not been for the illness, he may have lived his life in Kausar, as a barely literate farmer. Also, in retrospect Shiv Sahay’s decision to leave for the city was validated, had they stayed behind in Kausar there may have been more tragedies. This story of devastation in Shiv Sahay’s family due to disease was unfortunately very common in those days and there are other stories of entire families being wiped out.

The younger two brothers, Indradeo and Phuldeo, showed signs of academic brilliance while in school at Gaya and would have liked to continue their education to college. However this required them to move to a larger city and their father Shiv Sahay’s income was not enough to support this. The older brothers Gopalji and Baldev came to the rescue. Neither of them had gone to college after finishing high school and held low level jobs with the Government. But they willingly helped out their younger brothers, which I find very touching. In the next few decades there would be several instances were older family members took in their younger siblings to live with them while they were studying, and sometimes even paid for their tuition, probably at great financial hardship to themselves. A similar experience was recounted by my maternal uncle Yashwant Sinha in his own autobiograpy. Also being one of the younger ones in his family of eleven, he would not have been able to complete his own college education had it not been for the support he received from his older siblings.

My grandfather Indradeo (1884-1959) distinguished himself in academic work. He was a very diligent student: He was placed among the top students in Bihar in the high school finals exam, and after that he moved to Patna, finished his BA degree and then studied Law. He was placed 2nd in Calcutta University Law Exam around 1910, which was something that was still spoken of in the family when I was growing up in the 1960s. He started a law practice in the city of Chapra, not too far from Kausar, and within a few years established himself as one of the best attorneys there. The success of his law practice led made him financially well off and he built a beautiful house in Chapra sometime during the 1920s, which still stands.

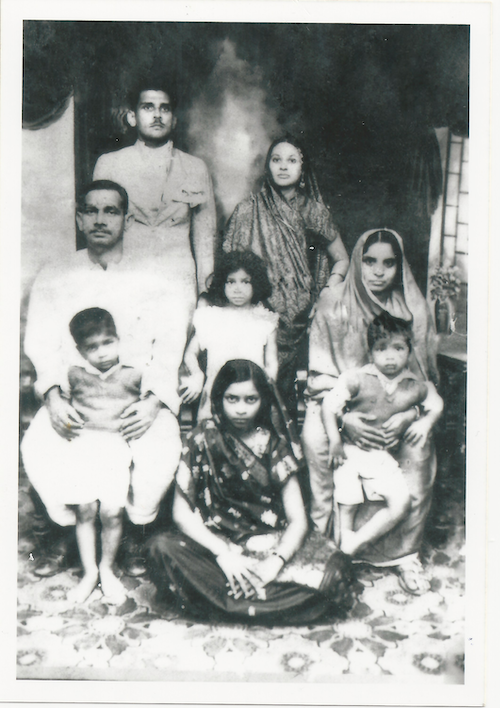

This photo of Indradeo’s family was taken in the mid-1940s. My father Birendra (on the left) and his fraternal twin Rajendra are the two boys standing in front of their parents, they were probably around nine or ten years old that time.

Indradeo passed away in 1959, but he left enough of a financial cushion for his family to continue living comfortably in Chapra and complete the education of Birendra and Rajendra, who were still in college at that time. I never met my grandfather since I was born in 1963, four years after his passing, but I grew up in the house that he built in Chapra, and lived there until I was six. His wife (and my grandmother) Girija, was like a second mother, and she ran the household after his passing, little changed from the time he lived there. It was quite a fascinating place, and as I realized later, the way of life was closer to way people lived in an earlier era, perhaps 100 years ago, than to the modern times. The home had a large central courtyard or angan, with a hand driven water pump in the middle, with all the other rooms were arranged around it. There was also a roof one could climb up to, which had the foundations of additional rooms which had been abandoned before they could be completed. I was told that the home did have a second storey once, but it came down in the Great Earthquake of 1934. There were still family members living in Kausar at that time, where they ran the family farm. I remember produce from the from Kauser coming to the Chapra every once in a while, after the harvest season. My parents moved away to Bombay in 1969, and then six years later in 1975, my grandmother passed away. The home was never fully occupied after that, and slowly deteriorated. My last visit to Chapra was in 1982. A few years ago the house was sold off, and no longer belongs to our family.

This brings us to the youngest brother and the author of the autobiography which serves as the source material for this family history – Phuldeo himself. After finishing his primary and secondary school education in Gaya, he studied for his BSc in Patna, then did an MSc in Chemistry at Presidency College in Calcutta (where he ranked 2nd among the graduating students) and then spent 2 years doing research at the Indian Institute of Science in Bangalore. He was the first in the family to study Science, a path that was then followed by his sons Satyendra and Shivendra, and also his nephew, my father Birendra. He spent most of his career at the Benares Hindu University, where he was a Professor of Industrial Chemistry, and later also served as the Principal of the College of Technology. Phuldeo Dada was the first in the family to study science (and apparently only the third in Bihar to do so), and served as an inspiration to his own sons, and also for my father, who all went on to study Science and Engineering, a trend that has continued with myself, and my children as well. He doesn’t dwell much in his autobiography about what inspired him to study science, a decision that he made while in high school.

During the 1970s I used to meet Phuldeo Dada quite often since he lived with his son Shivendra (Munnu) Chacha who was in New Bombay at the time when we were in Anushakti Nagar in Trombay. Both my father and Munnu Chacha had retured to India after finishing their PhDs in England, my father was a researcher with the Bhabha Atomic Research Center, while Munnu Chacha worked for the British multi-national company ICI. He later got transferred to Kanpur, and by co-incidence our family followed them there after a year or so. By this time I was older, and I got to know Phuldeo Dada better, and I was there in Kanpur at the time he passed away in 1981. A dear memory I have of Phuldeo Dada happened during the time towards the end of 1980, when he was very ill and already on his deathbed. The rest of my family had gone off to Patna to attend a wedding, I was alone at home, having stayed back because of school. Unfortunately I came down with high fever while they were away, and then decided to go to Munnu Chacha’s house. That night, as a I was tossing and turning with fever, I suddenly noticed Phuldeo Dada walk into my room, he was strapped with drips that were attached to a mobile fixture that he was dragging behind him. He obviously shouldn’t have been walking around, and he could hardly talk, but he wanted to know how I was doing.

Looking back, there were several factors that were influential in the family’s move from rural to urban life: Ramroop’s success in establishing a prosperous farming operation in Kauser that served as a base that the family could depend upon, Shiv Sahay’s willingness to uproot himself from a comfortable life in Kauser and spend almost two decades in Gaya to support his sons through their school years and the readiness with which the two older brothers supported their younger siblings through their college education. The fact that the younger brothers turned out to be academically gifted was a stroke of good fortune, but that by itself would not have been enough.